Abstract

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, ensuring product safety involves the detection and identification of microorganisms with human pathogenic potential, including Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium sporogenes, Candida albicans, and Mycoplasma spp., some of which may be missed or not identified by traditional culture-dependent methods. In this study, we employed a metagenomic approach to detect these taxa, avoiding the limitations of conventional cultivation methods. We assessed the groundwater microbiome’s taxonomic and functional features from samples collected at two locations in the spring and summer. All datasets comprised 436–557 genera with Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria accounting for > 95% of microbial DNA sequences. The aforementioned species constituted less than 18.3% of relative abundance. Escherichia and Salmonella were mainly detected in Hot Springs, relative to Jefferson, while Clostridium and Pseudomonas were mainly found in Jefferson relative to Hot Springs. Multidrug resistance efflux pumps and BlaR1 family regulatory sensor-transducer disambiguation dominated in Hot Springs and in Jefferson. These initial results provide insight into the detection of specified microorganisms and could constitute a framework for the establishment of comprehensive metagenomic analysis for the microbiological evaluation of pharmaceutical-grade water and other non-sterile pharmaceutical products, ensuring public safety.

Introduction

Water quality monitoring for microbial contamination is crucial for public health protection. Water is a universal solvent as well as the main ingredient in pharmaceutical products and can constitute a distinct source of microbiological contamination. In water-based environments, microorganisms, especially Gram-negative bacteria, can proliferate and develop even in the presence of extremely low amounts of nutrients. Therefore, stringent quality control should be in place to test water and liquid products used in the manufacturing of pharmaceutical products since the mere presence of water constitutes a high potential for microbial growth [1]. Non-sterile, water-based drug, and non-drug products are contaminated with opportunistic human pathogens that have resulted in product recalls within the United States (U.S.). A report surveying U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recalls from 2012 to 2019 [2] noted that Burkholderia spp. accounted for the greatest number of non-sterile drug recalls (105 recalls), followed by Ralstonia pickettii (45 recalls) and Salmonella spp. (28 recalls). Microbial contamination accounted for 77% of non-sterile and 87% of sterile drug recalls, indicating inadequate microbiology testing practices or faulty production practices. Most of the microbial contamination can be traced to pharmaceutical-grade water, as well as water distribution systems. Under the FDA Inspection Technical Guides (Water for Pharmaceutical Use|FDA), subject “Water for Pharmaceutical Use” non-potable water, potable water, purified water, and high-purity water are used in the manufacture of pharmaceutical products. Subsequently, water used in this process poses a serious risk of microbiological contamination of the final products, particularly in cases where proper testing procedures are not followed. The presence of certain microorganisms in non-sterile preparations has the potential to reduce or even inactivate the therapeutic activity of drug products and to adversely affect human health. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) < 1111 > sets acceptance criteria for the presence of certain microorganisms in non-sterile preparations based on the route of administration [3]. Furthermore, USP < 60 >, < 61 >, < 62 >, and < 63 > tests are designed to demonstrate compliance with these requirements by quantifying the presence of specified microorganisms [4,5,6,7]. More recently, the FDA pharmaceutical microbiology manual [8] has advised manufacturers to identify specified microorganisms. Current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) require only that viable bacteria are not recovered from products; therefore, only culture-based methods (i.e., for determining sterility and microbial limits) are considered cGMP. Additionally, USP has traditionally relied on the least common denominator of growth-based cultivation for testing methods [3, 9].

Historically, investigations of microbial communities have relied on culture-based methodologies. However, less than 1% of bacterial species in environmental communities are thought to be culturable on standard laboratory growth media [10]. For example, although BCC bacteria can grow and remain viable in hot or cold distilled water, most cells perish when transferred to trypticase soy broth (TSB) medium [11]. Recently, we recommended the use of oligotrophic media that allow for improved recovery of BCC organisms present in distilled water or antiseptic samples [12]. Improved detection techniques are needed to ensure pharmaceutical product quality and patient safety since BCC are capable of growing in low-nutrient conditions, resistant to antimicrobials, and have pathogenic potential [13].

Metagenomic DNA sequencing assesses the presence and the relative abundance of microorganisms, offering a more comprehensive view of the genetic complexity of natural and engineered microbial communities [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. As such, this approach seems appropriate for testing for the presence of bacterial populations rather than growth-based methods to detect “specified microorganisms,” which may not be culturable. A significant benefit of this approach is the detection and identification of certain microorganisms, including BCC, in pharmaceutical manufacturing that were previously missed or not identified by culture-dependent methods. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the potential of an incorporated metagenomics approach used in water analysis of non-sterile pharmaceutical products to detect specific microorganisms.

While evaluating non-sterile pharmaceutical products, a variety of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea) may be found and/or encountered, including specified microorganisms at acceptable criteria levels found in both groundwater and water-based pharmaceutical products. In the study reported here, using metagenomic sequencing, we sought to detect eight taxa, namely Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium spp., Candida albicans [5, 6], BCC [4, 9], and Mycoplasma spp. (USP < 63 >) [7] in “real-world” (potable and non-potable) groundwater samples from two geographical locations.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Scheme

The experimental strategy to detect specified microorganisms in groundwater is outlined in Fig. 1. This strategy is composed of three steps,

- Step 1: Sampling, DNA extraction, and whole metagenome shotgun sequencing.

- Step 2: Metagenomic analysis, including taxonomic annotations and functional assignment, and.

- Step 3: Visualization of specific microorganisms, including statistics analysis to associate data.

Overview of the metagenomic analysis to detect specified microorganisms in groundwater. This process is composed of three steps: Sampling, DNA extraction, and whole metagenome shotgun sequencing (Step I), metagenomic analysis, including taxonomic annotations and functional assignment (Step II), and visualization of specific microorganisms, including statistics analysis to associate data (Step III)

Sampling

Groundwater samples were collected from two different locations (Table 1). At Hot Springs, we collected potable water, while the non-potable water samples collected at Jefferson, came directly from cold water wells without any treatment. Using a sterilized 5-L bottle, groundwater was collected from cold water wells on six occasions in the city of Hot Springs, Arkansas (AR) (Latitude: 34°51′52.83″, Longitude: −93°04′54.258″) and on six occasions in Jefferson, AR (Latitude: 34°31′6.992″, Longitude: −93°2′57.083″) between February and August 2022. The July samples were repeatedly tested to demonstrate the reproducibility of the assay or technique. For each of these 12 collections, a total of 10 L of groundwater were filtered through 10 membrane filters (0.2 μm × 45 mm, Whatman, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) [19].

Full size table

DNA Extraction and Whole Metagenome Shotgun Sequencing

Ten-liter groundwater samples were filtered (1 L per filter) using 0.2 µm rated (and higher) pore size Whatman Supor 200 filters (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Each filter was excised, then placed into 2-mL Qiagen PowerBead tubes, and total DNA was extracted using Qiagen DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The initial concentration of DNA was evaluated using a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Due to low DNA concentration of the samples, linear amplification was carried out for all 12 samples using a REPLI-g Midi kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). The linear amplified DNA was cleaned using DNEasy PowerClean Pro Cleanup Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and concentrations were evaluated (Table 1) using the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit. Approx. 50 ng of DNA was used to prepare the library using Illumina DNA Prep (M) Tagmentation library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s user guide by MR DNA (www.mrdnalab.com Shallowater, TX, USA). The samples underwent simultaneous fragmentation and addition of adapter sequences. These adapters were utilized during a limited cycle PCR in which unique indices were added to the samples. Following the library preparation, the final concentration of the libraries (Table 1) was measured using the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit, and the average library size (Table 1) was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The libraries were then pooled in equimolar ratios of 0.6 nM and sequenced with 150-bp paired end for 300 cycles using the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Metagenomic Analysis

The paired end sequenced files were uploaded to the MetaGenome Rapid Annotation Subsystems Technology (MG-RAST, v3.0 (http://www.mg-rast.org) server by MR DNA (www.mrdnalab.com Shallowater, TX, USA) [24, 25]. MG-RAST is an open source, open-submission platform used to perform taxonomic and functional analyses of environmental datasets. Taxonomic annotations of the metagenome reads were performed against RefSeq databases. Subsystems under SEED were used for functional abundance analysis. All the annotations were performed using the default parameters in the MG-RAST pipeline (maximum e value of 10–5, a minimum identity of 60%, and minimum alignment length of 20 bp). Taxonomic assignment for the bacterial domain was done at phylum and genus levels. The SEED subsystem-based functional assignment was retrieved by applying filters at various hierarchical levels of classification to compute relative abundance of genes involved in different metabolic functions. For resistome profiling, the metagenomic dataset were analyzed for reads grouped at ‘Resistance to antibiotics and toxic compounds’ (level 2) of ‘Virulence, Disease, and Defense’ (level 1) of the SEED subsystems annotation. Level 3 and function-level subsystems were also analyzed for a deeper understanding of the resistome profiles.

Visualization of Specific Microorganisms and Statistics Analysis

Based on the best taxonomic assignment for the bacterial domain, considering an Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium spp., Candida albicans, BCC, and Mycoplasma spp., each sequence was classified into its genus level using Microsoft Excel. Alpha-diversity metrics were calculated using Microsoft Excel [26], which included observed species, Shannon, Simpson, Pielou, and Abundance-based Coverage Estimator (ACE); the observed species index measures the number of species per sample; ACE indexes estimate species richness; Shannon and Simpson indicate species distribution diversity and evenness. A Venn diagram calculates the intersection(s) of the list of elements (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Pearson correlation, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), and heatmap comparison were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v.10.0). Statistical differences in the functional annotation of level 3 subsystems were visualized using the GraphPad Prism 9 software package.

Results

A total of 12 sequencing results were obtained from six water samples from Hot Springs and six from Jefferson, generating a total of 71,185,593 sequencing reads. After removing sequences of low-quality (percent identity < 60), 52,958,916 sequencing reads were used for bacterial diversity and community analyses (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1) and 18,226,677 reads for functional analysis (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S2). In this section, we will evaluate the taxonomic composition, characterize a major metabolic pathway, and assess the presence of specified organism of the water sampled.

Full size table

Overview of the Metagenomic Data

In the Hot Springs groundwater samples, the average of reads was lower than that found in Jefferson groundwater samples. Specifically, the groundwater samples obtained in Hot Springs in July showed lower diversity indexes compared to the other groundwater samples collected in Hot Springs. The diversity in the groundwater microbiomes of Jefferson were similar in each sample.

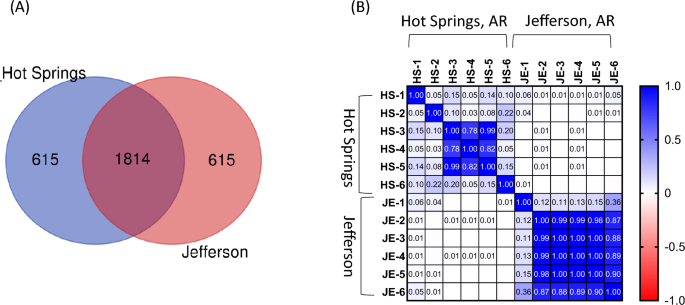

Subsequently, shared and unique reads were analyzed among groundwater samples collected in Hot Springs and Jefferson. Figure 2(a) shows that 1814 reads were shared among the two sampling sites. Moreover, 615 reads were uniquely found in Hot Springs and Jefferson. The complete composition of annotated reads is shown in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials. Figure 2(b) shows the correlation between all species (n = 2432) in the Hot Springs and Jefferson samples based on Pearson’s correlation analysis. In Hot Springs, the correlation coefficient of July (HS-3, HS-4, and HS-5) samples was above 0.78 (P > 0.05). However, coefficients with February (HS-1), June (HS-2), and August (HS-6) were lower compared to other samples. In Jefferson, the correlation coefficients of June (JE-2), July (JE-3, E-4, and JE-5) and August (JE-6) samples were above 0.87 (P > 0.05), whereas coefficients with February (JE-1) were lower compared to other samples.

Number of reads of annotated species in cold water samples collected in the city of Hot Springs and Jefferson from February to August 2022. a Venn diagram of the number of reads in different groundwater samples. b Heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficients at the genus level

Taxonomic Composition of Groundwater Microbiomes

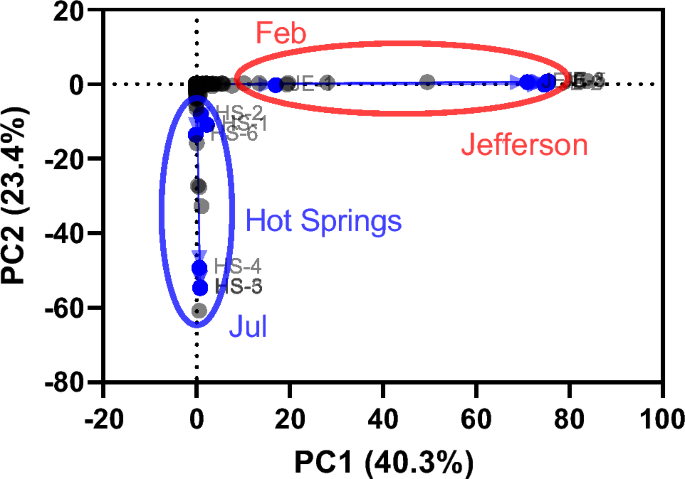

PCoA based on parallel analysis revealed significant differences in the microbiome composition of groundwater samples collected in Hot Springs and Jefferson from February to August 2022 (Fig. 3). In PCoA, it is noteworthy that the microbiota composition of HS-1 (Feb), HS-2 (Jun), and HS-6 (Aug) in Hot Springs, as well as JE-1 (Feb) in Jefferson, exhibited a stronger correlation, in line with the Pearson correlation results. This correlation was more pronounced when compared to the microbiota composition of HS-3, HS-4, and HS-5 (Jul) in Hot Springs and JE-2 to JE-6 (Jun to Aug) in Jefferson.

The structural composition of groundwater samples was characterized at the domain level (Supplementary Fig. S1a, b). All three domains, in addition to viruses, were identified in the groundwater samples. Bacteria were dominant in HS-1 (Feb), HS-3 to HS-5 (Jul), and HS-6 (Aug) with a relative abundance of > 79%, except for HS-2 (Jun) samples collected in Hot Springs (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Similar results were also obtained with JE-1 (Feb) samples collected in Jefferson (Supplementary Fig. S1b). However, the most abundant domain in Jefferson was either bacteria (36–74%) or archaea (24–62%). Furthermore, archaea were more represented in the structure of the Jefferson samples than in the Hot Springs samples. Within Hot Springs, the HS-2 sample was characterized by a dominance of the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota phyla, with some contribution from the HS-6 sample. Among the source groundwater type, the patterns were similar for both types of groundwater samples, only archaea were slightly more abundant (0.3%) in groundwater samples. In all groups, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria were the main five phyla (over 95% of relative abundance) (Supplementary Fig. S1c, d). Overall, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidota were the two most abundant phyla at both sites. However, the abundance of other phyla (Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria) was higher in groundwater samples HS-1 (Feb) and HS-6 (Aug) collected from Hot Springs (Supplementary Fig. S1b). In addition, the abundance of Proteobacteria in groundwater samples of HS-3 to HS-5 (Jul) was higher than in HS-1 (Feb) and HS-6 (Aug) in Hot Springs, whereas the relative abundance of Proteobacteria showed a constant trend in groundwater samples collected in Jefferson.

Characterization of Functional Groundwater Microbiome

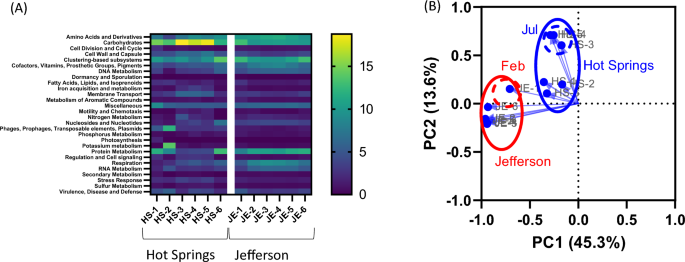

Metagenome functions were predicted using GraphPad based on level 3 of a subsystem function. Figure 4a shows the heatmap of the 28 levels 1 subsystem functions of the groundwater microbiomes in samples, whereas Supplementary Table S2 summarizes level 1, level 2, level 3, as well as their respective functions. The most prevalent among these are level 1 subsystem functions, accounting for 15.7% ± 2.8% carbohydrates (ranging from 11.8 to 18.8%) and 9.9% ± 2.2% clustering-based subsystems (varying from 7.5 to 13.9%) in cold water samples collected in the city of Hot Springs. In contrast, these functions were primarily represented as 10.6% ± 1.2% and 10.9% ± 1.5%, respectively, in Jefferson groundwater samples. The 10.6% ± 0.7% amino acids and derivatives (9.7–11.6%) were also contributed groundwater samples collected in Jefferson. In contrast, the subsystem function of virulence, disease and defense was predicted in 3.8% ± 1.3% (2.3–4.5%) and 3.5% ± 0.8% (2.8–5.1%) in Hot Springs and in Jefferson groundwater samples, respectively.

Heatmap a and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) b of relative abundance of the 28 abundant metabolic pathways (subsystem function) in the metagenomes found in groundwater samples from Hot Springs and Jefferson, AR

Predictive subsystem functions were used to generate a PCoA plot. Water samples collected in Hot Springs and in Jefferson clustered separately (Fig. 4b). Consistently, in PCoA of the microbiome composition, HS-1 (Feb) and JE-1 (Feb) clusters were more separated from HS-3, HS-4, and HS-5 (Jul) clusters from groundwater samples collected in Hot Springs and JE-2 to JE-6 (Jun to Aug) clusters from Jefferson groundwater samples, respectively.

In ‘Resistance to toxic compounds’ (level 2) from ‘Virulence, disease, and defense’ (level 1), cobalt–zinc–cadmium resistance was predicted mainly in Hot Springs groundwater samples to be 1.1% ± 0.9% and in Jefferson groundwater samples to be 0.95% ± 0.4%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). Arsenic resistance was predicted to 0.2% ± 0.3% in Hot Springs groundwater samples and 0.25% ± 0.1% in Jefferson groundwater samples, respectively. Furthermore, resistance to antibiotics (level 2), including multidrug resistance efflux pumps and BlaR1 family regulatory sensor-transducer disambiguation were observed at a comparable relative abundance in between Hot Springs (0.56% ± 0.5% and 0.42% ± 0.3%) and Jefferson (0.39% ± 0.4% and 0.67% ± 0.1%) groundwater samples. The relative abundance of beta-lactamase, erythromycin resistance, fosfomycin resistance, methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus, multidrug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni (CmeABC operon), multiple antibiotic resistance MAR locus, polymyxin synthetase gene cluster in Bacillus, resistance to fluoroquinolones, and resistance to vancomycin was relatively lower than 0.13% in both Hot Springs and Jefferson groundwater samples.

Presence of Specific Microorganisms

We observed totals of 436–525 and 561–557 genera in groundwater samples collected from Hot Springs and Jefferson, respectively. Among these, we identified all eight of the microbial taxa we sought (i.e., Burkholderia spp., Escherichia spp., Pseudomonas spp., Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus spp., Clostridium spp., Candida spp., and Mycoplasma spp.) in both Hot Springs and Jefferson. Escherichia spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Salmonella spp. belong to the Gammaproteobacteria Class; Burkholderia spp. belong to the Betaproteobacteria Class in Proteobacteria phyla; Staphylococcus spp. and Clostridium spp. belong to the Bacilli Class and Clostridia Class in Firmicutes phyla, respectively. Mycoplasma spp. belong to the Mollicutes Class in Mycoplasmatota phylum. Candida spp. belong to the Saccharomycetes Class in Ascomycota phylum in the Eukaryota Domain.

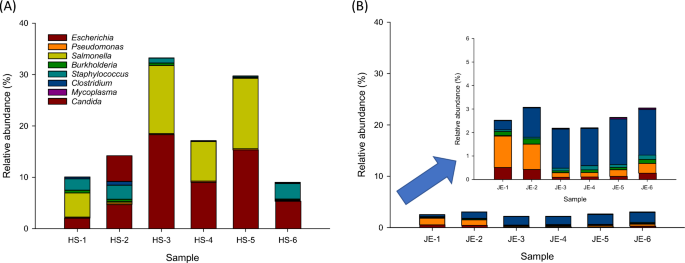

The genus-level relative abundance of specified microorganisms was observed less than 18.3% of relative sequencing read abundance in Hot Springs and Jefferson (Fig. 5). By calculating the percentage of the shared genera detected in Hot Springs versus Jefferson, we observed that Escherichia and Salmonella were mainly detected in groundwater samples collected in Hot Springs with 9.1 ± 6.4% and 6.6 ± 6.0%, relative to Jefferson (Fig. 5a). Clostridium and Pseudomonas were mainly identified in groundwater samples collected in Jefferson with 1.5 ± 0.6% and 0.6 ± 0.5%, relative to Hot Springs (Fig. 5b). In Hot Springs groundwater samples (Fig. 5a), Staphylococcus spp. Candida spp., Burkholderia spp., Clostridium spp., and Pseudomonas spp. were observed 1.5 ± 1.3%, 0.9 ± 2.0%, 0.3 ± 0.2%, 0.2 ± 0.3%, and 0.2 ± 0.1%, respectively. Mycoplasma spp. were observed very rarely at 0.004 ± 0.01%. In Jefferson, Escherichia spp., Burkholderia spp., and Staphylococcus spp. were observed 0.3 ± 0.2%, 0.14 ± 0.1%, and 0.12 ± 0.05%, respectively. Salmonella spp., Candida spp., and Mycoplasma spp. were observed less than 0.04% (Fig. 5b).

Detection of specified microorganism genera in the analyzed groundwater samples from Hot Springs a and Jefferson b. Results are expressed as relative abundance of reads

Discussion

The concern about “specified microorganisms” in pharmaceutical products is not a new public health issue and has been addressed in the general scientific literature, including in FDA publications. Microbial examination of non-sterile pharmaceutical products is performed according to methods recommended in the texts of U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) < 60 >, < 61 >, < 62 >, < 63 >, and < 1111 > [3,4,5,6,7]. The use of conventional culture-dependent methods is limited by their low sensitivity. In fact, we found that the Jefferson water samples contained less than 104 CFU/mL using 1/10 Tryptic Soy Agar (1/10 TSA) and TSA, whereas no growth was observed in the Hot Springs water samples. Additionally, neither of the studied water samples yielded any growth in Burkholderia cepacia selective agar (BCSA; bioMérieux), indicating the limitations of the conventional approach to recovering these organisms (data not shown). However, metagenomic analysis utilizes high-throughput sequencing techniques to identify specific microorganisms and to explore how these microorganisms adapt functionally within cold drinking groundwater environments. Metagenomic analysis can provide new insights into rapid diagnostics and monitoring, which, when applied as a manufacturing process control to analyze failures in non-sterilized pharmaceutical products, may be useful in protecting public health. In that perspective, an initial study was conducted using groundwater samples from two locations between February and August 2022 in order to assess the presence of specified microorganisms using a metagenomic approach. July samples were subject to repeated measurements as technical replicates which demonstrated the reproducibility of the metagenomic assay. The genus-level relative abundance of specified microorganisms was observed less than 18.3% of relative abundance. Escherichia, Salmonella, Clostridium, and Pseudomonas were mainly detected in Hot Springs and Jefferson.

Consistent with previous work, we identified bacteria, eukaryotes, archaea, and viruses in groundwater samples [19, 23, 27]. Bacteria were the predominant group in Hot Springs groundwater, with the exception of one sample in which fungi (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) were dominant taxa. The observation that fungi dominated just one out of six samples seems to corroborate the findings of Grabinska-Loniewska et al. [28], which suggested occasional fungal contamination of water samples. The occurrence of Ascomycota in groundwater samples has also been attributed to the formation and propagation of spores. These spores have a tendency to aggregate with each other and with other particles making them more resistant to water disinfectant treatment compared to bacteria [27]. In Jefferson, bacteria and archaea were predominant, which is in agreement with previous results [19]. Triplicates of groundwater samples collected in July 2022 from Hot Springs as well as Jefferson shared a similar composition, which is expected from biological replicates.

Proteobacteria have also been reported as the most abundant phylum in the municipal drinking water distribution system [20, 21]. Additionally, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria comprise the majority of bacterial communities in drinking fountains, sparkling natural mineral water, non-mineral bottled water, and tap water [19]. In contrast, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes have been found to be more prevalent than Proteobacteria in biofilms, bulk water samples, and drinking water distribution systems [23]. Cyanobacteria and Bacteroidetes were observed to be the two major bacterial phyla during a bloom in a drinking water treatment plant [29]. In this study, Proteobacteria were identified as the most dominant phylum in Hot Springs and Jefferson samples. It is worth noting that while Jefferson’s non-potable water contained fewer than 4% of these specified organisms, the potable water source in Hot Springs harbors over 15% of them. Interestingly, there is a clear difference between results obtained in February 2022, June 2022, and in July 2022. Compared to July samples, those collected in February harbored mainly Actinobacteria and Cyanobacteria. It has been reported that microorganisms respond differently to environmental changes that affect the microbial community diversity and composition with substantial fluctuation throughout the four seasons [30, 31]. This may be due to seasonal differences between those two time points, with a cold and drier period occurring in February (average temperature 8.3 °C, average precipitation 104.14 mm), compared to higher average temperatures and higher rainfall in July (average temperature 27.7 °C, average precipitation 106.68 mm) (Hot Springs, Arkansas Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)). In contrast, such variation was not observed in Jefferson groundwater.

Carbohydrate-based level 1 subsystems showed the highest relative abundance in groundwater from Hot Springs and Jefferson. Carbohydrates are an important energy source for essential growth, metabolism, and function. Clustering-based subsystems was the second relative abundant subsystem. Clustering-based subsystems are located in the genetic regions that are collocated to functional genes in the genomes of different taxa, but their functions are not well understood [32]. Amino acids and derivatives were the third most abundant level 1 subsystem. The biogeochemical cycle of nitrogen, sulfur, and organic matter are linked to functional features of the microbiome. Therefore, further investigations of some of the chemical properties of the collected water samples remain necessary. However, virulence, disease, and defense subsystem showed a low relative abundance in Hot Springs and in Jefferson groundwater samples. The relative abundance of level 2 subsystems in virulence, disease, and defense ranged between 2.35 and 3.01% in anaerobic and aerobic sludge [33] and sediment [34]. The groundwater reservoir showed high relative abundance of this subsystem at 9% [35]. We observed a prevalence of bacterial virulence genes to be higher in Hot Springs (drinking fountain groundwater) samples compared to Jefferson samples (groundwater). Microorganisms in Hot Springs groundwater samples were more closely associated with human activity compared to Jefferson groundwater samples. Human activity affects susceptible pathogens, leading to the proliferation of genes associated with virulence, disease, and defense subsystem.

At level 3 subsystems of resistance to antibiotics and toxic compounds, all samples showed the presence of genes conferring resistance to antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides) and heavy metals (e.g., cobalt–zinc–cadmium resistance). In agreement with our results, it has been found that cobalt–zinc–cadmium resistance was found in the ocean (5.7%), in mangroves (23.5%), and in terrestrial (27.5%) ecosystems [36]. A similar observation was made in the hyperalkaline Lonar Lake in India [37]. Though cobalt and zinc are essential trace elements, they can be toxic at higher concentrations, which may therefore require detoxification or removal by cation efflux pumps and perhaps by chelation. Antibiotic-resistant genes (ARG) are linked to the presence of metals [38]. Consistently, the resistome was comprised of 19 of level 3 classifications, dominated by multidrug resistance efflux pumps (46.7%) and BlaR1 family regulatory sensor-transducer disambiguation (25.2%) [39]. Multidrug resistance efflux pumps and BlaR1 family regulatory sensor-transducer disambiguation were observed at a comparable relative abundance between the Hot Springs (0.56% and 0.42%) and the Jefferson (0.39% and 0.67%) groundwater samples. This aligns with the presence of ARGs in various environments, including those existing prior to the introduction of antibiotics [39]. This may also reflect the possibility that a small fraction of the total bacterial population is resistant to antibiotics. However, further investigations are necessary to evaluate the real effect of specific bacteria on water sources.

The current USP < 1111 > has recommended microbial limits for aqueous non-sterile products of less than 100 CFU/mL of bacteria, less than 10 CFU/mL of fungi and the absence of E. coli in 1 g or mL of water [3]. Furthermore, non-aqueous preparations for oral use have a total aerobic microbial count limit at 103 CFU/g or mL and a total combined yeasts/molds (i.e., Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium, Fusarium, Alternaria, Mucor, Rhizopus, Trichoderma, Saccharomyces, Candida, and others) at 102 CFU/g or mL, and the absence of E. coli in 1 g or mL of water. As for the FDA, Title 21 of Code of Federal Regulation (CFR) §165.110 only establishes limits for coliforms (1 CFU/100 mL) and E. coli (absence in 100 mL) [40]. However, in most cases, a sufficient amount for detecting the fastidious bacteria by culture was 103–104 CFU/ml [41, 42]. Meanwhile, Brumfield et al. [19] showed that Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria are the dominant bacterial phyla detected in bottled water. Subsequently, Betaproteobacteria, which includes Burkholderiales and Gammaproteobacteria were the most detected microorganisms in sparkling natural mineral bottled and non-mineral bottled water, respectively. In a separate study, even though Gammaproteobacteria were prevalent in sparkling natural mineral bottled water, E. coli or enterococci were not detected in any of the drinking water samples [19]. Proteobacteria were consistently identified as the dominant phylum (> 60%) with 16S rRNA sequencing, respectively, in both drinking and bottled water [31, 41]. Proteobacteria also encompasses 85% of the isolated bacteria using the culture-based approach [43]. Additionally, Proteobacteria accounted for more than 99% of the reads detected with Illumina sequencing. Interestingly, fecal indicator and coliform bacteria (E. coli or enterococci) have been reported in private well samples and drinking water sources [44, 45]. In the current study, specified microorganisms, i.e., Gammaproteobacteria Class (Escherichia spp., Salmonella spp., Pseudomonas spp.), Betaproteobacteria Class (Burkholderia spp.), Bacilli Class (Staphylococcus spp.), Clostridia Class (Clostridium spp.), Candida spp., and Mycoplasma spp., were detected in both sampling sites. The percentage of Gammaproteobacteria was greater in Hot Springs than in samples from Jefferson. The highest proportion of Deltaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria was found in Jefferson. The strong presence of these specified microorganisms in both Hot Springs and Jefferson highlights the advantages of the metagenomics analysis in providing a comprehensive view of microbial population. However, it is worth noting that this approach does not discriminate bacterial OTUs that originate from viable and non-viable cells. Recently, Liu et al. [46] successfully discriminated between live and dead bacteria in human saliva and feces samples through the combination of PMAxx (an improved version of propidium monoazide [PMA]) treatment followed by DNA extraction and metagenomic analysis [46]. The PMAxx treatment, combined with our metagenomic approach, could provide better assessment to ensure effective monitoring of specified microorganisms in pharmaceutical-grade water. These results show the advantage of exploiting microbial fingerprints in assessing the quality of water used in manufacturing of non-sterile pharmaceutical products. Water being the most important raw material in pharmaceutical settings, it is recommended that it be periodically tested for the presence of bacteria in order to remain compliant with drinking water standards.

Conclusion

Overall, this study contributes to a better understanding of the structure and function of groundwater microbiomes in Hot Springs and Jefferson, AR. Using shotgun metagenomic sequencing, genus Escherichia (including Escherichia coli) and Salmonella (including Salmonella enterica) were among the specified microorganisms that were detected mainly in Hot Springs. In Jefferson, genus Clostridium (including Clostridium sporogenes) and Pseudomonas (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa) were most often identified. The presence of specified microorganisms in groundwater is undesirable due to their pathogenic potential. Multidrug resistance efflux pumps and BlaR1 family regulatory sensor-transducer disambiguation were observed as the major resistance pathways. This study provides insight into the groundwater genetic pool and the function of the genes involved. The research also suggests practical applications for the implementation of upgraded methodologies, and seasonal (periodic) evaluations to microbial risk analysis of water sources used for pharmaceutical products. Our non-culture-based monitoring techniques were unable to distinguish live from intact dead cells in bacterial samples. Future work will aim at counting viable microbes in unprocessed as well as processed water. This will enable us to assess the levels of viable bacteria cells we might expect to see in processed water used in the production of pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Dr. Carl E. Cerniglia for his years of assistance and support. We also thank Drs. Huizhong Chen and Seongwon Nho for critical review of the manuscript. This research was supported in part by an appointment of the Research Participation Program (S. Daddy Gaoh) at the National Center for Toxicological Research administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Food and Drug Administration.

Funding

This research was funded by the United States Food and Drug Administration.

Authors and Affiliations

Division of Microbiology, National Center for Toxicological Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 3900 NCTR Road, Jefferson, AR, 72079-9502, USA

Soumana Daddy Gaoh & Youngbeom Ahn

Division of Systems Biology, National Center for Toxicological Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Jefferson, AR, 72079, USA

Pierre Alusta

Department of Natural Sciences, Albany State University, Albany, GA, 31707, USA

Yong-Jin Lee

Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, USA

John J. LiPuma

Eagle Analytical Services, Houston, TX, 77099, USA

David Hussong

Office of Pharmaceutical Quality, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, 20993, USA

Bernard Marasa

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.G., Y.-J.L., D.H., B.M., and Y.A.; methodology, S.D.G. and Y.A.; data analysis, S.D.G., Y.-J.L., and Y.A.; writing–original draft preparation, S.D.G., P.A, Y.-J.L., and Y.A.; writing–review and editing, S.D.G., P.A.., Y.-J.L., J.J.L, D.H., B.M., and Y.A.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, B.M. and Y.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Youngbeom Ahn.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This manuscript reflects the views of its authors and does not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable as the study does not imply the use of any human or animal samples. This article does not include any studies on human participants or animals conducted by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Halls N (2004) Effects and causes of contamination in sterile manufacturing. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Jimenez L (2019) Analysis of FDA Enforcement Reports (2012–2019) to determine the microbial diversity in contaminated non-sterile and sterile drugs. Am Pharm Rev. https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/518912-Analysis-of-FDA-Enforcement-Reports-2012-2019-to-Determine-the-Microbial-Diversity-in-Contaminated-Non-Sterile-and-Sterile-Drugs/. Accessed 2 Aug 2023

USP<1111> (2016) Microbiological examination of non-sterile products: acceptance criteria for pharmaceutical preparations and substances for pharmaceutical use. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/harmonization/gen-method/q05c_pf_ira_33_2_2007.pdf. Accessed 2 Oct 2023

USP<60> (2018) Microbiological examination of nonsterile products – tests for Burkholderia cepacia complex. http://www.usppf.com/pf/pub/data/v445/CHA_IPR_445_c60.xml. Accessed 2 Aug 2023

USP<61> (2016) Microbiological examination of nonsterile products – microbial enumeration tests. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/harmonization/gen-method/q05b_pf_ira_34_6_2008.pdf. Accessed 2 Oct 2023

USP<62> (2016) Microbiological examination of nonsterile products – tests for specified microorganism. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjQjN3Zm8D0AhX8mXIEHen5AVwQFnoECDgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.usp.org%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fusp%2Fdocument%2Fharmonization%2Fgen-method%2Fq05a_pf_ira_34_6_2008.pdf&usg=AOvVaw21foqxGW8T3xSPTCa4F-3s. Accessed 2 Oct 2023

USP<63> (2016) Mycoplasma tests: a new regulation for Mycoplasma testing. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/harmonization/gen-method/q05b_pf_ira_34_6_2008.pdf. Accessed 2 Oct 2023

FDA (2020) Pharmaceutical microbiology manual. https://www.fda.gov/media/88801/download. Accessed 1 Nov 2023

Jimenez L, Jashari T, Vasquez J, Zapata S, Bochis J, Kulko M, Ellman V, Gardner M, Choe T (2018) Real-Time PCR detection of Burkholderia cepacia in pharmaceutical products contaminated with low levels of bacterial contamination. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 72(1):73–80. https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2017.007971

Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH (1995) Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev 59(1):143–169. https://doi.org/10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995

Carson LA, Favero MS, Bond WW, Petersen NJ (1973) Morphological, biochemical, and growth characteristics of Pseudomonas cepacia from distilled water. Appl Microbiol 25(3):476–483

Ahn Y, Lee UJ, Lee YJ, LiPuma JJ, Hussong D, Marasa B, Cerniglia CE (2019) Oligotrophic media compared with a tryptic soy agar or broth for the recovery of Burkholderia cepacia complex from different storage temperatures and culture conditions. J Microbiol Biotechnol 29(10):1495–1505. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1906.06024

Ahn Y, Gibson B, Williams A, Alusta P, Buzatu DA, Lee YJ, LiPuma JJ, Hussong D, Marasa B, Cerniglia CE (2020) A comparison of culture-based, real-time PCR, droplet digital PCR and flow cytometric methods for the detection of Burkholderia cepacia complex in nuclease-free water and antiseptics. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 47(6–7):475–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-020-02287-3

Garner E, Davis BC, Milligan E, Blair MF, Keenum I, Maile-Moskowitz A, Pan J, Gnegy M, Liguori K, Gupta S, Prussin AJ 2nd, Marr LC, Heath LS, Vikesland PJ, Zhang L, Pruden A (2021) Next generation sequencing approaches to evaluate water and wastewater quality. Water Res 194:116907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.116907

Schloss PD, Handelsman J (2005) Metagenomics for studying unculturable microorganisms: cutting the gordian knot. Genome Biol 6(8):229. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-229

Berry D, Xi CW, Raskin L (2006) Microbial ecology of drinking water distribution systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol 17(3):297–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.007

Beraud-Martinez LK, Gomez-Gil B, Franco-Nava MA, Almazan-Rueda P, Betancourt-Lozano M (2020) A metagenomic assessment of microbial communities in anaerobic bioreactors and sediments: Taxonomic and functional relationships. Anaerobe. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102296

Brown E, Dessai U, McGarry S, Gerner-Smidt P (2019) Use of whole-genome sequencing for food safety and public health in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis 16(7):441–450. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2019.2662

Brumfield KD, Hasan NA, Leddy MB, Cotruvo JA, Rashed SM, Colwell RR, Huq A (2020) A comparative analysis of drinking water employing metagenomics. PLoS ONE 15(4):e0231210. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231210

Farhat M, Alkharsah KR, Alkhamis FI, Bukharie HA (2019) Metagenomic study on the composition of culturable and non-culturable bacteria in tap water and biofilms at intensive care units. J Water Health 17(1):72–83. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2018.213

Saleem F, Mustafa A, Kori JA, Hussain MS, Kamran Azim M (2018) Metagenomic characterization of bacterial communities in drinking water supply system of a Mega City. Microb Ecol 76(4):899–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-018-1192-2

Roy MA, Arnaud JM, Jasmin PM, Hamner S, Hasan NA, Colwell RR, Ford TE (2018) A Metagenomic approach to evaluating surface water quality in Haiti. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102211

Douterelo I, Calero-Preciado C, Soria-Carrasco V, Boxall JB (2018) Whole metagenome sequencing of chlorinated drinking water distribution systems. Environ Sci Water Res Technol 4:2080–2091. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EW00395E

McLaughlin RW, Cochran PA, Dowd SE (2015) Metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota of the timber rattlesnake, crotalus horridus. Mol Biol Rep 42(7):1187–1195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-015-3854-1

Meyer F, Paarmann D, D’Souza M, Olson R, Glass EM, Kubal M, Paczian T, Rodriguez A, Stevens R, Wilke A, Wilkening J, Edwards RA (2008) The metagenomics RAST server – a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9:386. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-386

Hurle GR, Brainard J, Tyler KM (2023) Microbiome diversity is a modifiable virulence factor for cryptosporidiosis. Virulence 14(1):2273004. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2023.2273004

Douterelo I, Jackson M, Solomon C, Boxall J (2016) Microbial analysis of in situ biofilm formation in drinking water distribution systems: implications for monitoring and control of drinking water quality. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100(7):3301–3311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-7155-3

Grabinska-Loniewska A, Wardzynska G, Pajor E, Korsak D, Boryn K (2007) Transmission of specific groups of bacteria through water distribution system. Pol J Microbiol 56(2):129–138

Jalili F, Trigui H, Maldonado JFG, Dorner S, Zamyadi A, Shapiro BJ, Terrat Y, Fortin N, Sauve S, Prevost M (2021) Can Cyanobacterial diversity in the source predict the diversity in sludge and the risk of toxin release in a drinking water treatment plant? Toxins 13(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13010025

Sun C, Zhang B, Ning D, Zhang Y, Dai T, Wu L, Li T, Liu W, Zhou J, Wen X (2021) Seasonal dynamics of the microbial community in two full-scale wastewater treatment plants: diversity, composition, phylogenetic group based assembly and co-occurrence pattern. Water Res 200:117295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.117295

Pinto AJ, Xi CW, Raskin L (2012) Bacterial community structure in the drinking water microbiome is governed by filtration processes. Environ Sci Tech 46(16):8851–8859. https://doi.org/10.1021/es302042t

Gerdes S, El Yacoubi B, Bailly M, Blaby IK, Blaby-Haas CE, Jeanguenin L, Lara-Nunez A, Pribat A, Waller JC, Wilke A, Overbeek R, Hanson AD, de Crecy-Lagard V (2011) Synergistic use of plant-prokaryote comparative genomics for functional annotations. BMC Genomics 12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-S1-S2

Wang Z, Zhang XX, Huang KL, Miao Y, Shi P, Liu B, Long C, Li AM (2013) Metagenomic profiling of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in a tannery wastewater treatment plant. PLoS ONE 8(10):e76079. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076079

Curran JF, Zaggia L, Quero GM (2022) Metagenomic characterization of microbial pollutants and antibiotic- and metal-resistance genes in sediments from the canals of Venice. Water 14(7):1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14071161

Soriano BM, Del Valle-Perez LM, Morales-Vale L, Rios-Velazquez C (2018) Datasets generated by shotgun sequencing of metagenomic libraries of the guajataca water reservoir. Data Brief 21:2531–2535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.11.114

Imchen M, Kumavath R, Barh D, Vaz A, Goes-Neto A, Tiwari S, Ghosh P, Wattam AR, Azevedo V (2018) Comparative mangrove metagenome reveals global prevalence of heavy metals and antibiotic resistome across different ecosystems. Sci Rep 8(1):11187. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29521-4

Chakraborty J, Sapkale V, Rajput V, Shah M, Kamble S, Dharne M (2020) Shotgun metagenome guided exploration of anthropogenically driven resistomic hotspots within lonar soda lake of India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 194:110443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110443

Knapp C, Callan A, Aitken B, Shearn R, Koenders A, Hinwood A (2017) Relationship between antibiotic resistance genes and metals in residential soil samples from Western Australia. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24(3):2484–2494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7997-y

Imchen M, Kumavath R (2020) Shotgun metagenomics reveals a heterogeneous prokaryotic community and a wide array of antibiotic resistance genes in mangrove sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa173

FDA (2019) Title 21-Food and drugs chapter I-Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services Subchapter B-Food for human consumption. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, vol 2. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=165.110. Accessed 2 Aug 2023

Carraturo F, Del Giudice C, Compagnone M, Libralato G, Toscanesi M, Trifuoggi M, Galdiero E, Guida M (2021) Evaluation of microbial communities of bottled mineral waters and preliminary traceability analysis using NGS microbial fingerprints. Water 13(20):2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13202824

Boyapalle S, Wesley IV, Hurd HS, Reddy PG (2001) Comparison of culture, multiplex, and 5’ nuclease polymerase chain reaction assays for the rapid detection of Yersinia enterocolitica in swine and pork products. J Food Prot 64(9):1352–1361. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-64.9.1352

Sala-Comorera L, Caudet-Segarra L, Galofre B, Lucena F, Blanch AR, Garcia-Aljaro C (2020) Unravelling the composition of tap and mineral water microbiota: divergences between next-generation sequencing techniques and culture-based methods. Int J Food Microbiol 334:108850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108850

Stillo F, MacDonald Gibson J (2017) Exposure to contaminated drinking water and health disparities in North Carolina. Am J Public Health 107(1):180–185. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303482

Chen Z, Yu D, He S, Ye H, Zhang L, Wen Y, Zhang W, Shu L, Chen S (2017) Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in drinking water sources in Hangzhou city. Front Microbiol 8:1133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01133

Liu F, Lu H, Dong B, Huang X, Cheng H, Qu R, Hu Y, Zhong L, Guo Z, You Y, Xu ZZ (2023) Systematic evaluation of the viable microbiome in the human oral and gut samples with spike-in gram+/- bacteria. mSystems 8(2):e0073822. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00738-22

Original article location: Springer Nature